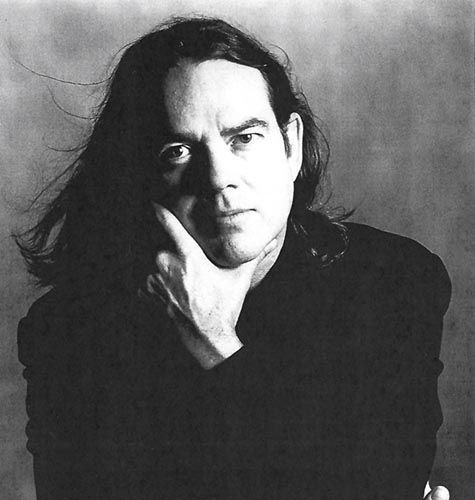

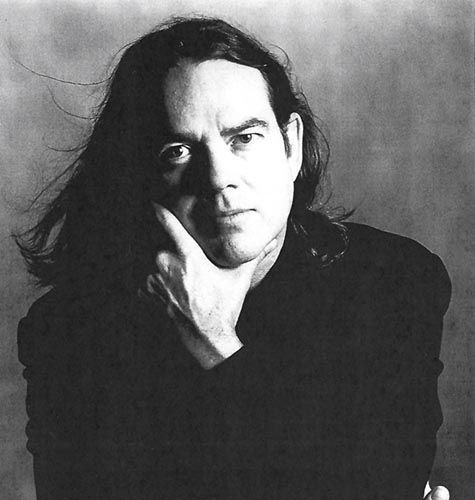

Gary James' Interview With

Jimmy Webb

What would the 1960s have been like without the songs of Jimmy Webb? He wrote "Up, Up And Away", "By The Time I Get To Phoenix", "Wichita Lineman", "Galveston", The Worst That Could Happen", "All I Know" and of course "MacArthur Park". Those songs have been recorded by everyone from Frank Sinatra to Barbra Streisand, to Johnny Cash, to John Denver, to Linda Ronstadt, to Art Garfunkel, to Richard Harris, to Donna Summer and

Glen Campbell. He was the youngest man ever to be inducted into the Songwriters Hall Of Fame in 1986 and named by Rolling Stone magazine as one of the Top 50 songwriters of all time. According to B.M.I. (Broadcast Music, Inc.) his song, "By The Time I Get To Phoenix" was the third most performed song in a fifty year time period spanning 1940 to 1990. He is the only artist to have ever received Grammy Awards for music, lyrics and orchestration.

Jimmy Webb has just written his autobiography titled The Cake And The Rain. (St. Martin's Press)

Q - Where does this talent of yours come from to write songs that have become so popular? This isn't something you can learn in any school. I maintain it's a God given gift and I believe somewhere along the line you've said the same thing.

A - Well, in my case I think it was a God given gift in more ways than one because I think it really originated in my work in the Baptist church with my father who was a minister and my mother's dream that I would become the church pianist. She really beat me to her will. It wasn't necessarily any idea of a career choice. When I was 12, 13 years old I started playing actually as the church pianist. I had come along and I could read music. It's like when I started improvising operatories and long pieces to fill in during funerals weirdly enough, different places where incidental music was needed that I first had to come up with my own arrangements, my own versions of say "Amazing Grace". I still don't play it the same way twice. So this improvisational skill, I sort of discovered that I had this ear and I could remember things fairly easily and I could improvise on them. That's really the germ of creativity. That's where you begin to learn to create your own little tunes. Sometimes it's very primitive. Sometimes it's very unsophisticated, but as time went by I became a great fan of some of the writers I was hearing on the air, particularly Hal David and Burt Bacharach. In my home, listening to Rock 'n' Roll was sort of a covert activity. My father wasn't really into Rock. So it became kind of a subversive thing as well. It was a way for me to act out against my father. So there were a lot of chemical things feeding this sort of drive. Somewhere along the way when I was 13, 14 years of age, I had solidified this goal which was I was going to make my living as a songwriter. A lot people thought I was just fooling around. I was a brat that knew how to play the piano, but I wasn't fooling around. From that moment on I was determined that that's what I was gong to do.

Q - The reason you most likely weren't taken seriously is because a lot of people want to be songwriters and so few succeed. You were one of the rare guys who actually did succeed.

A - I'm also lucky. I arrived at the scene probably at the most propitious time that I could have possibly arrived which was Hollywood in 1964. My college, my institution of higher learning was Jobete and Mowtown Records, which is where I really went into the studio. I wrote forty-five songs for Jobete Music. I'm not talking about Detroit. I'm talking about the West Coast.

Q - You wrote your first song at 13?

A - Yeah. That's about right, for someone else and eventually got it recorded.

Q - Would it have been a Rock 'n' Roll song?

A - No. It would've been like a Boudleaux Bryant, Everly Brothers type of ballad. You can hear it. It's on Artie Garfunkel's album "Watermark".

Q - Is it easier to write a follow-up hit song after you've written the initial hit song?

A - Well, I used to practice writing follow-ups before I was ever in the record business. My ear was agile. I was aware that artists were following their hit records with let's say copies of those records, or versions of those songs that were different, but not so different that it wasn't recognizable as the same artist and in some cases it was certainly the follow-ups. And that's what they were called. The follow-ups were strongly reminiscent of the original record. Obviously this was a commercial ploy to sell records and possibly create another hit based on the success of the first one. Being aware of this, first on an instinctive level and later being absolutely certain that this was what was going on, 'cause my ears weren't lying to me, I began doing my own follow-ups for The Everly Brothers or I would do a follow-up for Elvis Presley. I would do a follow-up for anybody because I was just by myself in a room. I could do anything I wanted. A lot of those songs obviously no one ever heard because my father had banned me to the garage. (laughs) But I got a lot of practice writing follow-ups before I ever got serious about finding a job with a publishing company. I mean, I did a lot of preparation. When I went up to Hollywood when I was 17, I left home. My father and I had went our separate ways. At least temporarily. I went up to Hollywood and finally landed this job at Motown. When I walked in there I must've had fifty songs that I knew were passable.

Q - You told Robert Hilburn of the L.A. Times in 1971, "From what I've seen of this business there is a tendency for songwriter, once they have become successful, to stick to a formula." So, we just talked about that. There are two guys who I would say broke that formula. Their names are John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Would you agree?

A - They were extremely versatile and that's why they're on my list of favorite songwriters. It was also two guys. It wasn't just one guy. Paul was off into the music hall stuff, which is kind of funny to do. It was kind of sending up some of the music of our ancestors. It was John I think who was more serious who sort of created some of the early psychedelic masterpieces. Together they managed to turn out an amazing array of very versatile and different sounding songs. It's very hard to look around and find someone who compares to that. If you think about The Kinks, you think about a certain kind of song. The Rolling Stones took some chances. They did some renaissancey arrangements and some folky things that they did, but they immediately backed off of that and went back to rockin'. Their songs are definitely in a groove. Very hard to mistake them for somebody else. Those are just two examples, but the industry is rife with examples and that's where success was. Broadcasters like to know before they put the record on, they liked knowing to some extent what they were getting into.

Q - I read somewhere that every songwriter should have a Glen Campbell singing his songs.

A - (laughs) I think that was probably me.

Q - You were right on with that one! He did play a big part in your success, didn't he? Having a guy like Glen Campbell singing your songs?

A - Well, yes. I do a show called The Glen Campbell Years, which is really devoted to him and kind of devoted to our relationship. It's about a fifty year relationship and his extraordinary musicianship and a kind of almost phantasmagoric affinity between his voice and my songs, considering that we had never met until the Grammy Awards in 1968, at which point we still didn't talk. I didn't really get to know him until well after I'd written "Wichita Lineman" for him. That song I wrote specifically for him. It was easy. He used to say, "It just fit." I was a big fan from the age of 14. I remember hearing the first hit record by Glen on Crest Records. It was called "Turn Around Look At Me". I was a big fan and started writing Glen Campbell songs right away. I wrote 'em for year with no real hope that he would ever hear any of 'em, but as fate would have it we came together. We came together again. I was prepared. I had Glen Campbell songs. Glen used to say something that is apropos of what we're discussing. Glen used to say, "Luck is when preparation meets opportunity."

Q - That's true.

A - And I was deeply prepared. While the other guys were out playing football and baseball and had girl friends and motor scooters and things like that, I was really at home writing songs. I don't know how I was able to do that. I look back on it and it was by no means a normal childhood. It was a childhood more like perhaps a piano prodigy, but it was self-imposed. Nobody forced me into a room and said, "You have to write songs all day long everyday." When I arrived in Hollywood I had prepared myself. A lot of things I didn't know experientially. I had a long way to go, but signing up with Motown as a staff writer was one of the most brilliant things I ever did in my life. At Motown, they knew more about cutting hit record and writing hit songs than just about anybody on the map and I was right there when they were red hot and they were very kind, if not loving, towards me. I think I was kind of a mascot over there 'cause I was so young. I was one of the only White kids in the building and they wanted to teach me. I'll leave a lot of it right there at Motown because they knew how to cut hits. They knew how to take a song that was kind of flat and work on it a little bit and turn it into something special.

Q - Before going to Hollywood, had you been in a band?

A - I always wanted to be in a band. I gigged with bands when I was in high school, at Colton High School out in the San Bernadino area. I was with two different bands. The first one was a Jazz quartet. This is pre-Beatles and we were playing a lot of the Jazz standards of the day, Dave Brubeck. We'd do "Take Five". We'd play fraternity parties. We had little matching coats. We did well. We would pull down twenty bucks a piece on a weekend, which for us at that particular time and place was survival for us. My family was long gone at that point. I was hanging on to those gigs. Then I got into a bigger band called Four More, which was more electrified and we were doing covers. I played with them for a while, but ironically once I got to Hollywood things began to happen for me. I drifted farther and farther away from the band idea and couldn't really seem to get back. I had sidemen who played with me on the road, but the entity of a band, of being in a unit where we were all equal partners and the camaraderie and the sense of sort of teamwork of doing something together, was something I missed because I never really got back to it. I was always kind of a loner. Eventually you get used to being a loner and it doesn't seem like a bad thing. Eventually you become proud of being a loner and sort of confident in you own ability to do things, which again is something that can turn around and bite you right in the ass. Everybody needs help. Everybody needs a second opinion, especially in the world of music because you can so easily delude yourself into believing that something is great just because you've got it up on the speakers and it must be great 'cause you did it. So, I think I missed out a little bit in not having a real intimate contact with a full-time unit of sidemen. I played (with) The Wrecking Crew all the time. They played on virtually all my records and I was close with them, but I never really toured with them. I became kind of an outlier, a floater.

Q - If you had a songwriting partner he would almost have to have been with you from the beginning. After your success to say to someone, "You're going to write with Jimmy Webb," it would be too intimidating.

A - (laughs)

Q - It's like someone saying, "Sit down with Paul McCartney and write a song."

A - That's very kind of you to make that allusion. My problem with collaboration was always that I could never stand to be in a room with somebody else for that long. It's not because I thought I was better than everybody else. It's really painful for me to write songs. I make a lot of mistakes. I run up a lot of false tributaries trying to find my way to the source. I'm very self-conscious. Just painfully shy about; to this day I'll wait for my wife to go somewhere then I'll go into the living room and sit down and maybe I'll try to write something. I think it was the early years of writing the way I did, sort of in seclusion in the garage and sort of not singing too loud because I didn't want my father to hear my singing about girls and love. He didn't think much of it. Until I was firmly established as a songwriter, then he began to take an interest in what I was doing. Before that he thought I was wasting my time. So I grew up pretty much in a room by myself. I collaborated. I wrote with

Gerry Beckley of America one time. I used to write with Kenny Loggins every once in a while. He was family. He was practically my brother-in-law. That's a long, complicated story. He was family. And it would have to be family. It would have to be somebody that was really, really close to me to let my guard down, to expose ideas when they weren't fully flushed out.

Q - Couldn't you rent office space somewhere and bring in a piano and write there? You wouldn't have to wait for you wife to leave.

A - Yeah, I could do it and I've done it. It's more than speaking literally. I was trying to paint a picture for you of what my attitude is. I'm getting ready to do another solo album and I've got songs to finish and I think I may very well need to go to the studio near here and work in a back room where they have little electronic instruments. Just go in there and spend some time because that seems to be the way that things really happen for me. I connect to another source. I think we started out talking about God. I know that when I am open to these ideas, I'm in kind of an altered state. I'm in kind of an alpha state. When I'm in that state and I'm receptive there seems to be almost a conduit, a way of absorbing ideas that almost don't seem to originate with me. They seem to be originating somewhere, some distance removed from me. It's quantum physics, emotional quantum physics. I have to be in that state, be totally open for this to work. It doesn't work like being a riveter, here's my rivets, here's my rivet gun. It's not like that at all. It's something I can't explain. I have to ease into it. I'll play the piano sometimes for a couple of days, three days, beginning to create modalities and keys and place little niches to where I feel like I can work where I have a starting point and begin to work out. A lot of times I will work on chord structure before I work on anything else because there's no point in going on if you don't have that. If you don't have something that's deeply satisfying on a chordal level there's just no point in going on.

Q - Then the words will come to you.

A - They'll come to me or I will sit down somewhere and write and sort of channel them because I need them to complete (the song). It's one of the components from the whole songwriting process. This is a good idea for a song. Here's a verse and a chorus. Really that's all you need. You don't even need the chorus. Here's a verse and now I need to come up with some chord structure and a melody to get this thing started. Then for me the writing, the actual construction, the imagery and the story telling has always been a very natural thing for me. I just wrote a memoir that originally was 300,000 words. It comes out April 17th, 2017 and is called The Cake And The Rain. It's published by St. Martin's Press. It was very much like having all the impedimenta of songwriting. It can only be two verses. It's gotta be under three minutes. It's gotta be all of that. Having all of that removed including the melody and the stricture of having to be in a particular scansion and being on the beat, making sure it's a proper rhyme. All these sort of rules and regulations that I impose on myself to get the results that I need and sitting down and just writing open-minded was a pure joy. I mean, it was joy. It was ecstasy. It was a lot of hard work, but the time went by quickly. The first thing I knew I had enough for three or four books. I sort of feel myself being pulled more in that direction as I mellow and I move into a different time of life. I think what a delightful prospect it would be to just write. Just have that freedom to write. To play with words and to tell stories, to sort of fully enjoy myself as an organ, as a pure writer, because the songwriting things comes with a lot of rules and regulations.

Q - Well, it used to. Songs today don't seem to have much of a melody and the words leave a lot to be desired.

A - I might as well tell you flat out that I strictly disapprove of that. I don't consider it proper songwriting. I would never write that way. I could never take any satisfaction from throwing songs together the way people do these days.

Q - It must drive you crazy then.

A - Well, a lot of it just feels like nursery rhyming. Couldn't you come up with a better line than that? In twelve hours couldn't you come up with something besides that? Yeah, I feel that way. I know immediately I'm branded as an old fart and irrelevant and all that, but I don't care. A lot of it is just not very good. I grew up in a business where songwriting was respected and it was an art. You earned the respect of people around you by creating within certain parameters. You told a story. You exercised a great deal of skill in your choice of words and the way you rhyme things or didn't rhyme things. Your songs went from A to B. There was a narrative. I feel like I'm wasting my time even talking about it. But because it is so far gone at this point, to me, and I know this is what my father said 'cause my father used to say during the Elvis Presley era, "All the songs sound the same to me," and I never really had a lot of sympathy for him. I thought obviously these are different songs Dad. You're really screwed up. I would never say that to him. Much of this Top 40 kind of dance music that I hear is so similar, and I have a pretty good ear, I really have trouble sorting out which record is which.

Q - What about Country music?

A - I think Country music has hit a slippery slope. It's been so overly influenced by Pop music. That was a flirtation that they obviously thought, the powers, thought was worth taking on because of its commercial appeal and you would sell to a wider group of people by sort of rocking a little bit more and then even being a little more nonsensical. If you look back into the history of Country music you will find some of the greatest songwriting that Americans have ever done. Hank Williams, Don Schlitz, "The Gambler". That stands like a monument out in Monument Valley. Every word, every line had a purpose. It had a motive force behind it. It carries the listener onward. You were absorbed in the story. Something has happened in Country music and Pop right now. When I think about it I try to analyze what it is that I'm bitching about. It's a disconnect with any attempt to rationalize the lyrics. The lyrics are just sort of a fabric that's draped over the record. You could take the lyrics away or you could just translate them into some other language and nobody would really care because they're not poignant. They don't reach into your soul like some of the old, great constructs of Country music that had twists and turns of fate in them. They had little word play. They had puns. They had all kinds of lyrical intricacies that were part and parcel of the Country song experience if you will. For some reason there is a devaluation of the currency of lyric writing. It's just not something that gets a lot of attention or energy.

Q - Does it bother you when people ask you what your songs mean? Does it upset you? Does it get you mad?

A - No, not really. Actually I've got a pretty good sense of humor about things like "MacArthur Park". I have still not come to the end of the interpretations of "Wichita Lineman". It goes from everything from people thinking it's about football. One woman thought it was about a lineman who died up in the wires and was still hanging on a wire. The other night a guy walked up to me after a gig and said, "Thanks for Wichita Lineman. All of us truckers really appreciate it." (laughs) My mouth like fell open. I'm thinking this is a zero sum game. It doesn't matter what I say. Even if I did try to explain it, people hear what they want to hear. If I have any minor irritation it's about the cake and the rain. I get a lot of crap about that. I must've heard about a billion times if I had a dollar, "What does the cake out in the rain mean?" That's the sort of dispassionate version. "MacArthur Park" has detractors who have made violent attacks on it from the beginning, including Edward Saul of Newsweek magazine who did two pages on it on what a piece of crap it was. This is right after it came out. And it's been going on ever since. It's like in some way or another I have personally insulted them by writing this song. What irritates me, and it only is an irritation, is that all the songs of that era are equally if not more inscrutable. What is A Whiter Shade Of Pale? I don't know. Don McLean's The Day The Music Died. It's indecipherable. You need a code book to follow along. You need a concordance for "A Day In The Life" or "Strawberry Fields" or so many of these songs. That's not even talking about Bob Dylan, who's holding the Nobel Prize for literature and some of the absolutely incomprehensible lyrics that he wrote on his first three or four albums. So I just feel, why are you picking on me for Cake Out In The Rain? I know what it means to me. I think in this book in a sense I just got frustrated with it and said, "Okay, here's the cake out in the rain. Here's what it means. Here's how it came to be." It's a real place. Real things happened there. There's nothing in the song that I didn't see with my own eyes, physically see, and put out my own hand and touched everything in the song. And so, that's it. Every time I go out front after a gig, and I play all the time and I usually play pretty near capacity. Usually I'm playing (to) four to five hundred people now. I did fifty dates last year and every night I go out front to sign memorabilia. It's one of the things I do. It's one of my favorite things to do. I realize when I go out there that I'm going to face several people who are going to ask me, "What does the cake out in the rain mean?" (laughs)

Q - I'm glad I didn't bring up what I read Frank Sinatra said about that. He said something to the effect that it's one of the dumbest lyrics he ever had to sing.

A - Well, I don't know. I don't know if he ever said that or not, but he never said that to me.

Q - You would know!

A - (laughs)

Q - He never sung "The cake out in the rain." He sung the middle section, "After all the loves of my life", which is a classic '40s ballad. So, I don't know where that came from.

A - You were in college when your mother passed away. You dropped out of college then. Had your mother not passed, would your story be any different?

Q - I couldn't honestly say that it possibly would. It might have. She was very young. She was thirty-six years old. So, she was young enough to exercise a considerable influence over my life. I don't think she would've gone down the Rock 'n' Roll path with me or the Pop music path if you will. I don't think she would've gone willingly. She was very much adored and I don't know if I ran up against her one to one and she said, "I don't want you to do this," I don't know exactly what would've happened. I never had to make that decision. She never knew anything about any of this. Most it's a good thing. Probably my life would've been a lot more conservative had she been around. The family pretty much disintegrated with the absence of her personality. My father began to waiver in his beliefs about the ministry. My sister Janice immediately got married. In fact, my dad moved back to Oklahoma. He struggled on for a few years as a minister and finally came out to California and got in the record business. He was a pretty good record guy. I just don't know. It would be ridiculous of me to say it wouldn't have mattered because we knew any time we play around with the time/space continuum that something happens. Sometimes radical things happen from very, very small inputs. This was a rather large input, my mother's absence. I think it probably made me feel like I didn't have much to lose. There wasn't much at home for me anymore. If I'd been Herman Melville, that would've been when I would've gone down and signed up on the whaler and gone down to the South Pacific. I was going to do something with my life. I wasn't going to go back to Oklahoma and end up teaching Band somewhere in some province or necessarily become a farmer like my grandfather. Once she passed away I think there was a certain inevitability to my decisions and they all led in the same direction there. There was tremendous gravity pulling me towards this way of life, this opportunity to be a part of something which I had never been growing up. I think that's about as intimate as I want to get with you.

Official Website: www.JimmyWebb.com

© Gary James. All rights reserved.

Jimmy Webb

Photo from Gary James' Press Kit Collection