Gary James' Interview With

Malcolm Bruce

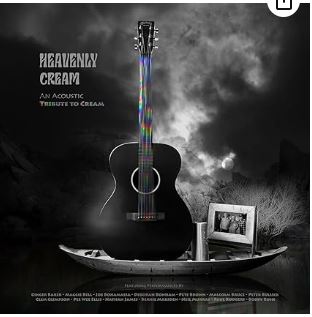

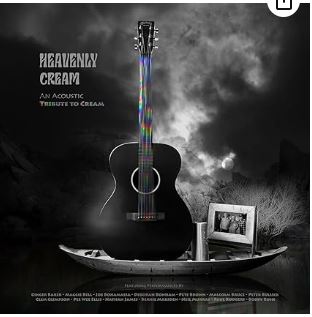

On November 3rd, 2023, Quarto Valley Records released a truly unique album titled "Heavenly Cream: An Acoustic Tribute To Cream". The album will be available on vinyl, CD and digitally on all platforms. The fifteen track tribute album features musicians Joe Bonamassa, Deborah Bonham, Malcolm Bruce, Peter Bullick, Nathan James, Bernie Marsden, Maggie Bell, Rob Cass, Clem Clampson, Paul Rodgers, and Bobby Rush. The first single off the album, "Sunshine Of Your Love" was released on September 1st, 2023.

That song was written by Cream bassist Jack Bruce and Peter Brown. An edited version of the song was released in the U.S. in December, 1967 and became the band's first single and highest charting American single. It entered Billboard's Hot 100 in January, 1968, reaching number 36. It was later named to Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Songs Of All Time, ranking number 65. We spoke with Malcolm Bruce, Jack Bruce's son, about "Heavenly Cream: An Acoustic Tribute To Cream".

Q - Malcolm, I've seen some reference books refer to Cream as The Cream. It's just Cream, isn't it? It's not The Cream.

A - Well, according to my dad it was actually The Cream. We talked about it, me and him. I heard him correct people sometimes. I think initially it was The Cream because they were sort of the three musicians who were seen as the cream of the crop as it were in the U.K. They were confident, put it that way. They played for years and came up the hard way as it were through the music circuit at the time. So yeah, I think it was The Cream, but I think as things went on they became known as Cream. I'm sure it just got to the point where my dad was just fed up with correcting everybody and just accepted it. (laughs)

Q - Whose idea was it to do this acoustic tribute to Cream? Was it yours? Is it acoustic because someone felt a remake of the original recordings could never measure up?

A - Well, it was Pete Brown, the Cream lyricist who passed away earlier this year (2023) in May. It was his idea with the record company, Quarto Valley Records. Pete was talking to them about a separate documentary about Pete's life and career called White Rooms And Imaginary Westerns, which I don't think has been released yet. It will actually be released next year (2024) at some point. That's a completely separate thing that's already been shot and edited with Martin Scorces and all three members of Cream included I believe. So, he was talking to Quarto Valley about that project. I think they then started discussing the idea of doing a tribute to Cream and shooting a documentary for that as well. I'm not sure if it was that specific as saying, "We're never going to do as well as the original guys." Although I would agree, it would be pointless to do the same thing because they're historic recordings now in that sense. I think we would all agree that there's something magical about that time. All the different bands that were recording then, there's no point in trying to be better than them. We could never do that. So, I think collectively the idea to do it acoustically was really just to have a fresh perspective on it. I hope that's what we've achieved. Here's a different way of looking at the music, to sort of shine a light on it in a slightly different way. Let the songs speak for themselves rather than all the wiggly, crazy guitar stuff we could have done. We just stripped it down. But I don't think it's an acoustic record. I don't think it comes across that way. I think it's still got punch and groove and all the things you would expect from that material. We just weren't allowed to play any electric instruments. (laughs)

Q - Is it your hope to reach people who might have never heard of Cream or their music?

A - Yes. I think it's always the hope. We're all part of a tradition. Music is about tradition. It's about a lineage you can trace back. You can trace the Blues back to all kinds of things and then all of the different influences that brought my father, Ginger and Eric together. In the wider context we're all part of a tradition. So, I think it's the maintenance of that. Obviously you've got the original people, people that are in their seventies now, who were around when Cream was around almost sixty years ago, and so we hope they will love this as sort of a fresh look at Cream's music. I think there's always that hope that younger generations will enjoy it as well and be attracted to it.

Q - How old were you when Cream was at the height of its fame?

A - I was minus a number of years. I wasn't born yet. (laughs) I don't even think I was an idea in my parent's minds at that point. So, I get off with flying colors with that. I wasn't really around until afterwards.

Q - And my next question would have been: Did you ever see your father perform onstage?

A - I never saw him perform in the original Cream. I played with him myself as I grew up. I was involved with many of his projects over the years as a musician. As a child, I saw him play. I was in a band, living in Hollywood in 1993 when they were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. So, I actually went along to the ceremony and they got up and performed. I think it was two songs that night. Then I was at The Royal Albert Hall for the Cream reunion in 2005 and then I was at Madison Square Garden as well. So, I did get to see them play, but not in the original time. It's a slightly different thing I guess.

Q - Did you ever ask questions about the band or the music to your father over the years?

A - We talked so much about music and all different kinds of things. I'm not sure if I asked direct questions about it. I think just growing up with a father like my dad, it was just something we would improvise together at home. As I became a teenager I was making my own music, writing my own songs. I was playing a number of different instruments and so he would encourage me. He would do things with me. I remember we actually made a record at home when he was getting into music technology when I was a kid. I was like fourteen, fifteen. He was buying sequencers and synthesizers, multi-track and all that kind of stuff. So, we actually made a record at home. There were pianos around. I got into piano from the age of five onwards, and then the bass and the guitar after that. But rather than being specifically, "So, how did you write the riff to 'Sunshine Of Your Love'?" or whatever, it was more just like music was the bond, the thing that bonded us. It was the thing that was always in our minds, our lives, our souls. It was just what was there. So, I think it was osmosis more than anything specific in terms of questions. I'm sure there were, if I was to dig into my mind, into my memory, I'm sure there were some questions along the way. (laughs) I'm sure plenty.

Q - Did your father play another instrument besides bass?

A - Yes. He played the piano and he played the cello and he played the Hammond organ, which was just another keyboard, but he enjoyed playing. He enjoyed playing the organ. I think that was pretty much it, but he could play some nice acoustic guitar as evidenced back in the Cream days with a song like, "As He Said". That's him playing guitar. He really enjoyed experimenting with open tunings just like Joni Mitchell. Joni tends to write using open tunings because it gives a unique perspective on harmony. So, my dad enjoyed doing things like that. He was a musician in that sense. In the '60s, like many people, he was being influenced by Indian music. He got himself a Veeno, which is like a bass sitar, and he started learning that. Some of his right handed technique on the bass guitar was influenced by the way those Indian instruments were strummed. So you can kind of see the technique he evolved from the Veeno to the bass. It's a beautiful instrument he fell in love with and explored to some degree. I wouldn't say he took that instrument as far as it can go, but he took elements of it into his own playing as a bass guitarist.

Q - Where did Cream practice? Did they practice in someone's basement? Did they have a rehearsal hall? Do you know the answer to that?

A - Wow! I could ask my mom because I believe there was a school hall they practiced in early on, like a girl's school maybe. Something like that. I think they might have rehearsed at Ginger's house, which is in Northwest London at a place called Neasden. I can check with my mom. She was around. She co-wrote two songs with Cream. She was around then and would know that information more than I would.

Q - I can tell that's a question you probably don't get too often.

A - It's a great question! They were well-known in the U.K. Obviously somebody had scrawled "Clapton Is God" in graffiti. They'd been in The Graham Bone Organization. They were well-known as musicians, but Cream was a whole other thing. They weren't rich, so it's a great question. It's like, "Where does a band start out before they're famous? Could they afford a room?"

Q - Would you know if the guys in The Beatles or The Rolling Stones ever passed through the doors of your father's house?

A - Oh, very much so, yeah. They all know each other. George Harrison appears on my father's first solo record, "Songs For A Tailor". He uses a pseudonym on that record. He calls himself, L'Angelo Misterioso. My mom has some stories about George turning up at our house. That first solo record was released in 1969, so a little after Cream. It's probably likely that they started crossing paths a lot more once Cream became really well-known. But certainly my father knew all those guys. He knew Paul. My dad was part of John Lennon's Lost Weekend, later on obviously. I'm friends with

May Pang, who I met in New York. My dad toured in Ringo's All Starr Band as well. In terms of The Beatles there's a direct connection with all of those guys. Eric and George were absolutely very close friends. They even shared a wife I believe. (laughs) They were that close! As far as The Stones go, yes. Charlie Watts was the original drummer in Alexis Korner's Blues Incorporated when my dad joined that band, which was in 1961 or 1962 I believe. When Charlie left to join The Rolling Stones, I believe he actually suggested Ginger as the drummer. Ginger took over the drum stool, or drum chair as they called it, in Alexis' band and played with my father. So, even before any of them were known at all, by anybody apart from a few fans at a club in London or whatever, my dad and Charlie knew each other. I spent three days with Charlie and my dad in the very early '90s at Simon Phillips' studio, the drummer. He lived down the road from us. We spent a few days recording demos with Charlie and he stayed at our house. My dad also had a band with Charlie called Rocket 88. I think that was in the '80s, which was really like a proper, authentic Blues type band. My dad knew Mick (Jagger).

Mick Taylor, who was the guitarist, obviously not the original guitarist, but he did "Exile On Main Street" with The Stones and joined my dad's band. So there were lots and lots of connections between all of those guys.

Q - Did your father know Brian Jones?

A - That's a good question. I can ask my mother that as well. She's the person to talk to.

Q - I always ask if people who were around in the late 1960s, early 1970s, knew Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix.

A - My dad absolutely knew Jimi Hendrix for sure. When I was a kid, one of my school friends was Stephan Chandler. His dad was Chas Chandler. So, when I was ten I got to know Chas really well. Later on, about twelve years ago, I met a guy called Neville Chesters when I was playing with Leslie West and Corky Laing. I was doing a gig at B.B. King's in Manhattan and this guy was sitting on the side of the stage and somebody introduced me to him, and they called him "The Little Brit." He was a fixture on the New York scene. But anyway, he was Jimi Hendrix's roadie. So, I got to know Neville. Neville passed away not long ago. I got to know him really well. He was very, very close with Jimi. So yeah, I think that's the funny thing about the music business. There's certainly those people that came from around that time. There was a very small core group of people that all seemed to know each other because it was a much smaller scene then. It was just a small group of people that championed Black, American music in the U.K. The avid kind of excitement of getting a record playing and finding out about it. Brian Jones was sort of one of the most important people early on to sort of champion that music in the U.K. Obviously there was Alexis Korner before that and Cyril Davis, the harmonica player, and

John Mayall a little later. It's fascinating because it was just literally a handful of people that invented this British "R And Boom", as they call it. Then suddenly, two or three years later they were all world famous and all you guys (Americans) were talking about them, (laughs) whereas before they were all talking about you.

Q - If you were a musician in England in the 1960s, that was the place to be!

A - Yes. There's a sociological way we can look at that I suppose. Certain post-war elements, the breaking down of class structures, the emergence of youth culture so that young people suddenly had an opinion. When you give young people a voice it gives young people some kind of power. Obviously I think the real infrastructure, the real power structures never changed, but at least on the surface it did. For a moment, there was a little moment there, a little window there where young people were able to express themselves and that's a very powerful thing. It's hormonal I guess. There's a very primal thing about that. (laughs) Now we're very much cynical. I imagine if you were around and you have those memories, the power of having electric guitars and the power of those kinds of statements, we don't really understand that. My generation were probably more cynical or probably just that we made assumptions that maybe earlier generations were just in awe of. I was lucky I got to work with Little Richard when I was staying in Nashville. I did a couple of days in the studio with him and it was just amazing to be around him. He was such an amazing person. He was really kind to all of us in the studio and very humble. But then I kind of went back and listened to his early music and it was just mind blowing. No one is ever going to be as good as that! I can't really explain it with words. There's a force in it. There's a power. There's an energy about it that's pure and maybe slightly unconscious. It's just coming from a deep, deep part of him, but he's just a vessel for it. It's really interesting stuff.

Q - Someone told me in the mid-1960s, in England, when one of The Beatles would walk into a restaurant with their wife or girlfriend, all the other famous musicians would stop eating and turn around and look.

A - (laughs)

Q - Can you imagine being that famous?

A - I suppose I experienced a little bit of that with my father, depending on who we were around. I've hung out with Ringo. The thing is, they're actually just normal people. When I met Ringo he was just really down to earth and polite. I met his wife, Barbara. They were really sweet people. When they were doing a gig with my dad, it was organized by Gary Brooke. He was in the band with my dad at the time. I sort of met Ringo before they did the show and we had a little chat and then they did the show. Later on, as he was leaving with his wife, they were just kind of walking out and he turned around and saw me and said, "Oh, Malcolm, nice to meet you. See you later." He actually took the time to say goodbye to me and yet it's Ringo! You think, "Wow! Ringo took the time to say goodbye to me." But at the same time, he's just being himself, like a normal person. I really respect him for that, that he hasn't lost being that kind of person. I'm sure there's another side to that. If you annoy him, he'd probably start acting like a Rock star, but the fact that he still considers other people in just a normal fashion shows how down to earth these people are. They're just people. They came from a working class background. They never had any pretensions to be world famous and suddenly they found themselves in that situation. Kudos to people who don't lose sight of that and they're still able to be successful.

Q - Did your father ever talk about why Cream disbanded?

A - I think the general feeling was that they had been overworked by (Robert) Stigwood and the management. They were touring all the time. They all got kind of tired. There was lots of elements. Ginger was a well-known heroin addict very early on and a registered heroin addict in the U.K., which meant that he had a prescription for his drugs. One of the things that was agreed between the three of them; it was Ginger's idea to put the band together. He went to Eric. Then Eric went to my dad. Eric said to Ginger, "I'd like Jack to be in the band." One of the provisions was Ginger had to give up taking drugs, taking heroin, and he did it. He said, "Okay," and he did stop taking heroin. I believe towards the end of the band he started taking heroin again, two and half, three years later. So maybe that had an impact. I don't know. It's s hard to tell isn't it with the dynamics of a band. I think Eric tended to be more in line with the Blues and kind of the American traditions in the more purest sense than my dad and Ginger. My dad was classically trained and came from Jazz as well. But my dad and Ginger discovered the Blues. I think there was a kind of tension between the three of them for that. I think that maybe Eric wasn't as comfortable with the more experimental side of what perhaps at times Cream were touching on. So, there was maybe a few little musical differences at times. Although from my point of view, and I'm sure from the people that listened to it, that's maybe what made it so special because it was a little more adventurous and experimental. They could all play. They could all actually improvise. No other band was doing that. Not in the way they were doing it, between the three of them, the synergy they had. Obviously there are other bands like The Grateful Dead and some other bands that were improvising and stretching out, but I think Cream had a very unique perspective on all of that. But I'm not sure if Eric was that comfortable with it in the same way that my dad and Ginger were. Obviously there's the famous Rolling Stone interview that Eric did that was quite critical in some way that maybe triggered Eric not wanting to do it anymore. I'm not sure. One of the things my dad always maintained was that the band was overworked. They were touring incessantly and didn't have any time off to write or recover. So I think maybe a combination of things.

Q - We don't see bands like Cream anymore. Is that because they don't seem to get the breaks that Cream got? And finally, the musicianship doesn't seem to be there in today's bands. What would you say to my observations?

A - (laughs) I think it's an issue with culture and economics and education where we arrived at a certain point. I would just extract that concept out of a specific genre of music and you can look at all genres of music and say we're getting a bit repetitive. Everyone tries to conform to something instead of blowing the lid off of it and discovering something new. I'm generalizing, but I think we are in a place of consolidation rather than really true innovation. I think that's a cultural thing. We're not encouraged to explore something new. Put it this way, if you're gonna try and put a band together, and you're gonna try and get a manager, and that manager is gonna try and get a booking agent and a record deal, what are those entities going to say? "Oh, man. I've never heard anything like that before! Give them all the money they need to become successful!" or "Wow! It sounds like a mixture of Ed Shearan and Aerosmith. So, we know the market." The market is so corporatized. The industry tends to play it save because they are trying to monetize something and it's a risk to put money into something where it's an unknown. Back then there was perhaps an age of innocence and naivety. "Okay, that's a little different. Let's do that." There are of course some innovative things happening. I'm making a new record that's coming out next July (2024). I hope that has some kind of impact to something new. But I think generally speaking, music has become somewhat predictable and safe and confined to this identity so it's salable with our market instead of going, "Let's have the courage to really break things down and do something new." Of course once in awhile I hear something that's mind blowing, but generally speaking if it's the Blues and you see a Blues band, it's what you expect. It's not breaking down something new. It's just the same old thing. It might be done brilliantly, but it's predictable. I can predict every phrase, every note. I can say I know how the voice will sound, how the guitar player and the bass player will sound. We're at kind of at a crossroads, but I think in a bigger perspective the whole of humanity is at a crossroads. It's all tired and obvious the way we're functioning on this planet right now. We need to have a long, hard look at ourselves and wake up. I think all of that has a huge impact on creativity, and each of us in our own small way can contribute to that.

© Gary James. All rights reserved.

The views and opinions expressed by individuals interviewed for this web site are the sole responsibility of the individual making the comment and / or appearing in interviews and do not necessarily represent the opinions of anyone associated with the website ClassicBands.com.